Fluid Technique: Aesthetica Interview

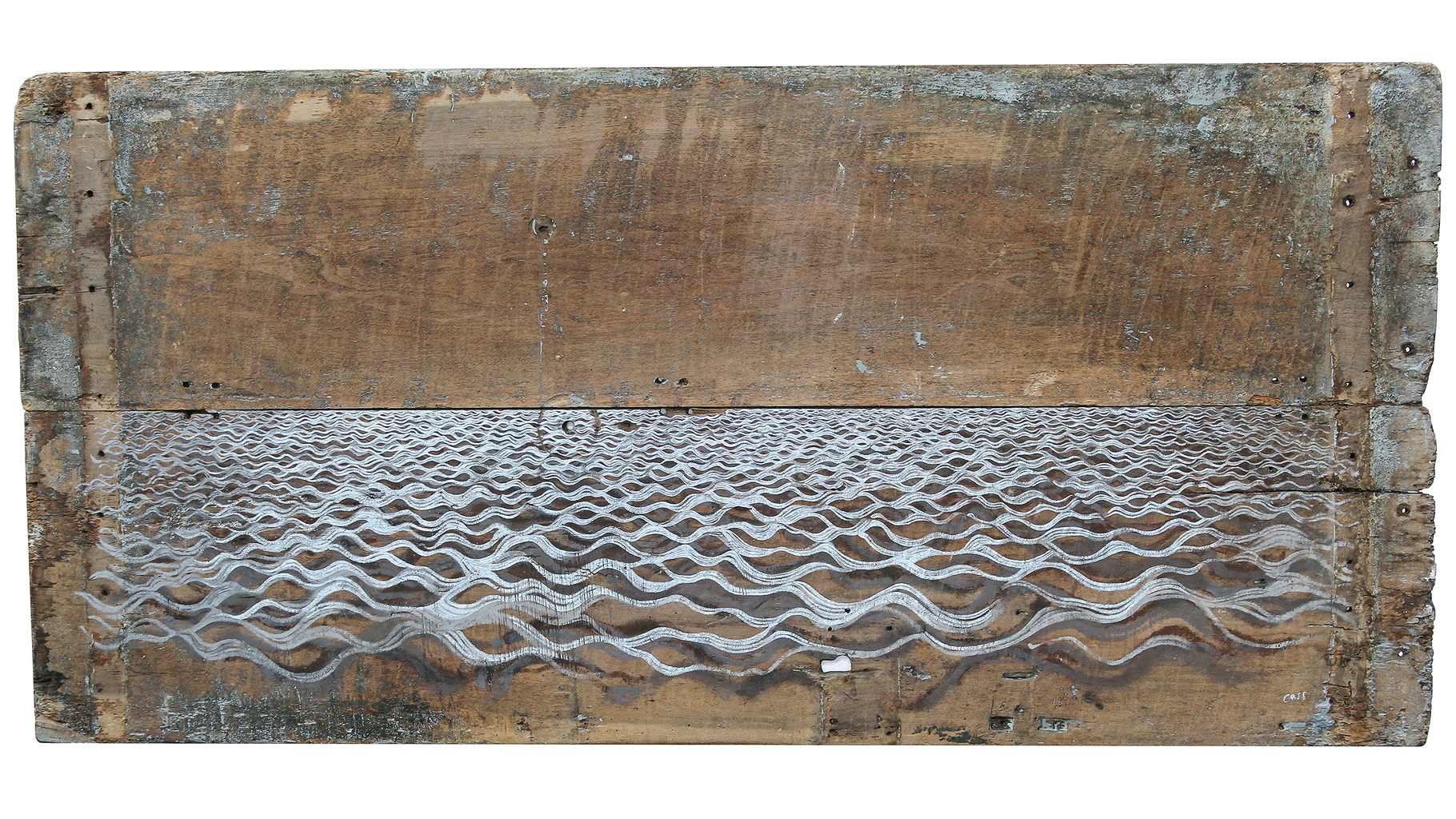

“Without exception, each of David Cass’ artworks describe water in some way. From straight depiction of seas or pools to exploration of environmental extremes in drought and inundation. His most recent works present the issues of modern day Venice in the face of rising sea levels and mass tourism. He works almost exclusively with found materials: as a type of alternative canvas on which to paint.”

A: Would you say your creative process begins when sourcing your found objects?

DC: My artwork is heavily process based: the act of gathering is equally as important as the action of painting or pulling research together. Travelling to gather antique items and objects is, yes, the starting point: days spent hunting down old wooden items, often from flea markets or antique fairs in France, Belgium, Germany, Spain, Italy … sourcing not only surfaces (substrates) on which to paint; but also inspiration from each location. Many of my artworks are site-specific. Some of my recent paintings of water were created using wooden materials (or paper ephemera) found in derelict homes in an arid-zone– abandoned due to a lack of water – thus pointing towards a process that is already in motion.

A: Do you have a clear concept in mind before finding your materials? Or do you let the materials lead the direction of the piece?

DC: By painting water (an endless motion) almost exclusively, I reference the past-lives of the objects with which I create my artworks. I use table-tops, doors, shutters, coffee-grinders and matchboxes to paint on: items used day-in-day-out, as part of a routine. A domestic ebbing and flowing. The manner in which I paint further enforces this theme: I work in layers, using deliberately repetitive marks, and so there is a clear link between surface and subject.

A: What is it about the nature of water that inspires you?

DC: Water lies at the core of all life, but so does balance. Water in abundance brings danger, yet when it’s in scant supply the same is true. My artworks aim to describe a semi-imaginary world, yet one which draws upon fact. This world is one that pulls past events to the present day, and does not distinguish between locations. In this world, sea-rise exists alongside desertification. Flooding exists alongside drought. Environmental extreme events from the previous century occur simultaneously to modern day extremes. Extremes being the operative word: for these works do not set out to convey the transient happy-medium, even if many of their aesthetics describe stillness.

A: How did your scholarship to Florence influence your practice?

DC: Primarily, the Royal Scottish Academy scholarship opened my eyes to Europe. To living and working on the continent, and bringing ideas home. Thematically, the scholarship introduced me to the history of a past environmental-event: a flood which devastated Florence in 1966. Since embarking upon a project exploring this catastrophic inundation, I’ve never looked back.

A: Your recent works have been concerned with the rising sea levels of modern day Venice. How do you aim to communicate this deeper level of ethical consideration within your work?

DC: My Venice project is a direct step on from my Florence flood investigation. Venice is Europe’s first clear victim of sea-rise: the city is the first to be almost completely inundated. Residents describe Venice as “dying amongst the waves of the Adriatic.”

Conversely, the Spanish province of Almería is the first European location to witness desertification. We are witnessing clear and scientifically proven environmental change in these locations. I aim to use these two opposite environments as a springboard, and basis for my work; which encapsulates painting, film, photography, documentation (digitalising of ephemera which relates to these settings) and writing. The result is not only an exploration of “wet” and “dry”, but also a poetic investigation of issues which will soon expand from being of local concern, to being widespread. My works range from being studies of fields in which crops have failed in Almería (and interviews with affected locals); to being painted examinations of Venice’s rising waterline or polluted lagoon surface, and the impact the rise is having on homes (and inhabitants).

A: You had an exhibition at The Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh, earlier this year – could you talk about the work displayed and how this show has helped to further your career?

DC: In January 2017 I had my fourth solo show with The Scottish Gallery. The gallery (in my hometown) took me on at my degree-show in 2010. Every artwork I’ve created since graduation aims to be connected through this illustration of water, either in its presence or its absence. As my practice has developed, simple depictions of ocean (transferred from hand to rejuvenated surfaces) have multiplied and increased in size, age and ambition. My painted bodies of water have filled and risen: thicker marks and more permanent paints have become flooding and over-spilling. From imagination in the case of my Overpaintings, through to historical fact in the case of my Florence, Venice and Paris flood works. I’ve exhibited key stages of the development process with The Scottish Gallery, and my next show with them will be in early 2019.

A: What projects are you working on currently?

DC: I’m currently spending time researching and sorting through unrealised project ideas. Most of this takes the form of film and photography (often my media of choice as a starting-point).