A Project by David Cass

In collaboration with Sam Healy

TILL · Version I · 2x Speed · Excerpt: 1972–2012

TILL is a generative artwork, constantly re-forming in response to data.

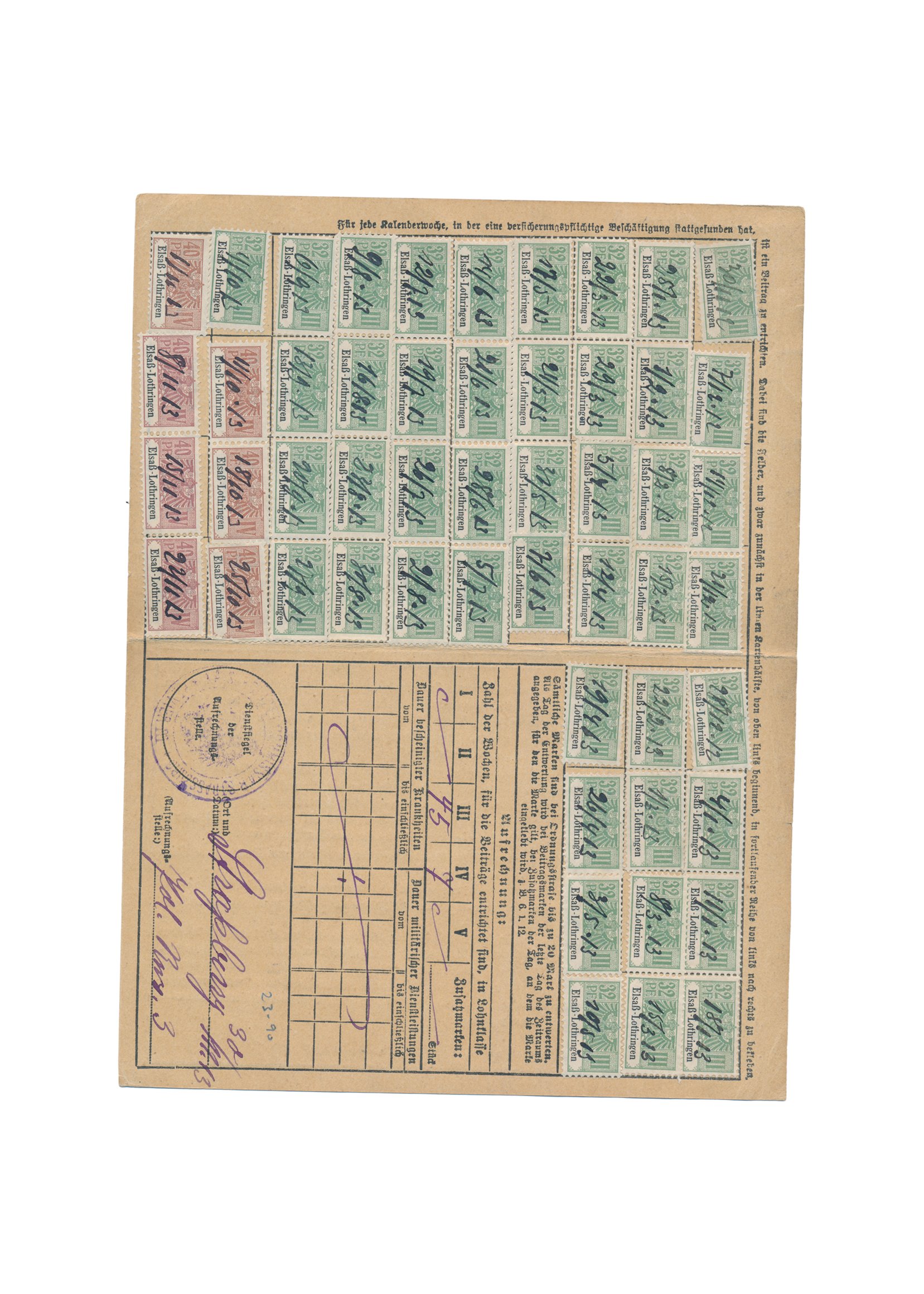

Light coloured found papers represent ice coverage; dark carbon-papers represent expanding sea.

TILL is a digital public artwork by David Cass, created in collaboration with Sam Healy. It’s a generative collage consisting of six variations in both landscape and portrait formats, created for exhibition and online screening. The piece imagines Arctic ice as a living entity, its fate inseparable from our own. It weaves together several threads from Cass’s wider practice: the use of antique materials, the manual act of letter-writing (as explored in Where Once the Waters), the integration of climate data, and the investigation of spatial division developed in Rising Horizon (2019–2020). The visual structure draws from As Coastline is to Ocean (2019), where found papers were assembled into layered topographies. The coastline – a recurring motif in Cass’s work – is presented here in a new form, as a moving aerial landscape shaped by real data. Healy’s experience with data gathering and interpretation make him the perfect collaborator for this project, he’s an artist dedicated to revealing beauty from within mathematical entities.

The title helps to gather the conceptual threads of the project: it is glacial and temporal, economic and archival. It refers first to glacial till – the raw debris left behind as sea ice retreats – a geological residue of loss. This mirrors the core of the work, which visualises Arctic sea-ice data from 1895 to present: a period of relative stability ruptured by industrialisation and followed by accelerating collapse. TILL focusses on summer sea-ice for two reasons: firstly, its seasonal melt is often studied as an independent indicator of climate change; it’s a microcosm of the broader crisis. Seasonal observation offers a focussed lens through which to understand global warming’s pace and impact.

Secondly, the artwork was first launched during the summer season and the Tall Ships Races 2025 hosted in Aberdeen. The city’s harbour, facing the North Sea, sits just south of the Arctic. One of the Race’s oldest vessels, the Christiania (1895), dated to the very moment this timeline of loss began. So, the ships became silent witnesses – floating timekeepers within the narrative arc.

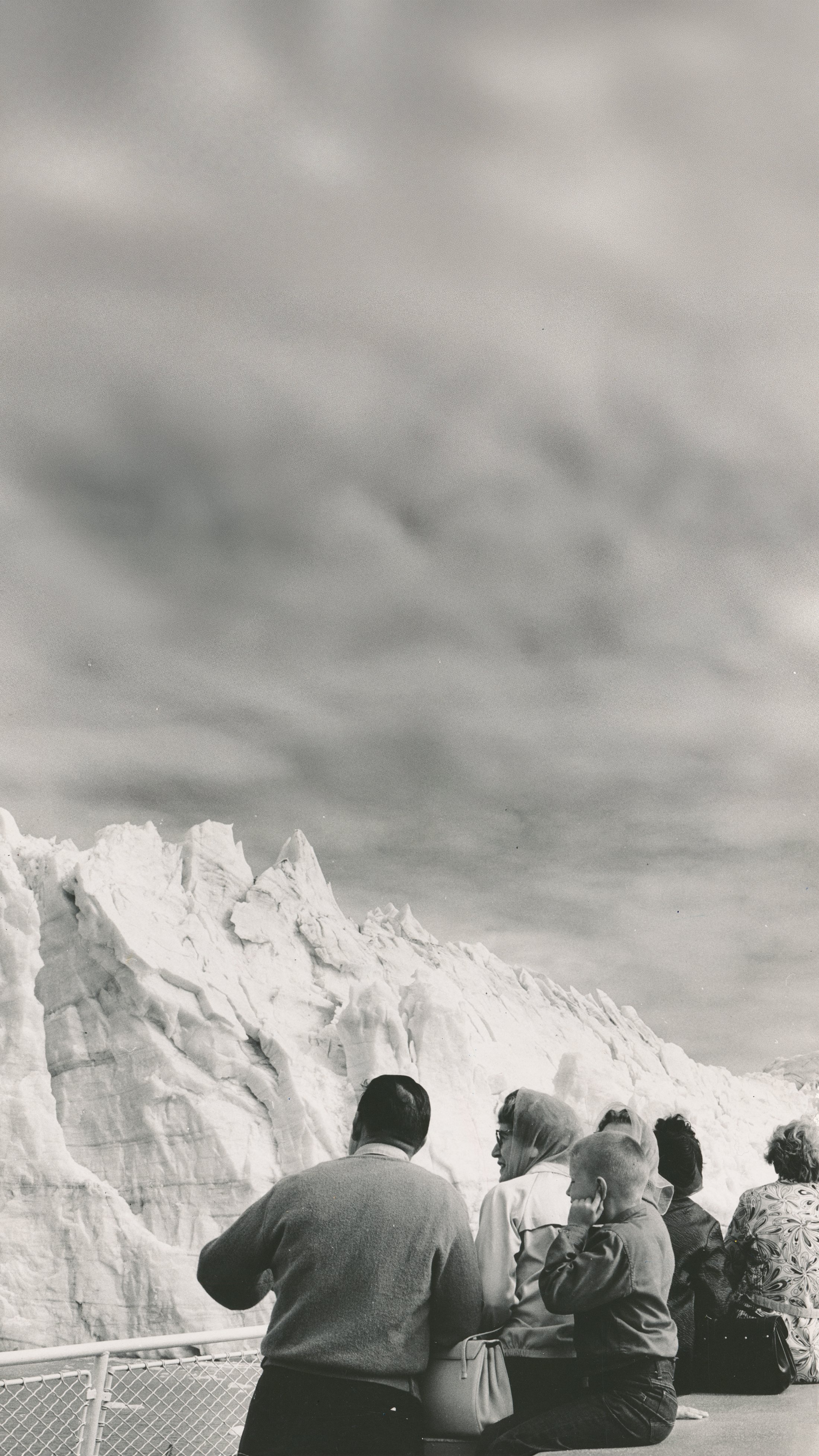

The artwork takes the form of a constantly re-shaping aerial coastline – a patchwork that shifts over time from full ice cover to a near-barren scene of dark, light-absorbing sea. Light papers (with their higher albedo) represent ice; dark carbon papers represent sea, chosen not only for their matt-black appearance, but their very name and material composition – which make them a fitting substrate for conveying a legacy of carbon pollution. TILL traces the diminishing extent of summer ice using real data: from early captains’ logs and whaling records to contemporary satellite readings. The result is a kind of alternative graph – an artistic rendering of environmental data. As years progress and ice cover diminishes, so too do the collage’s light papers.

TILL · Version II · Currently screening in Films of Return

Alongside the science and structure of the work sits a second kind of archive: personal, analogue, human. In Scots, the word till carries meanings of both accumulation and residue. The scanned papers which form this collage, then, are the till of life – letters, postcards, tickets, certificates – gathered and repurposed. If TILL had a soundtrack, it would surely be the voices of these papers, growing quieter as the years progress. These are more than ephemera – they are an accidental archive, compiled as we extracted minerals, burned oil, and warmed the Earth. They speak not only to what we did, but to what we stand to lose, and in many cases, how we’ll lose it. Travel brochures, oil adverts, blueprints, endless receipts, and hundred-year-old photographs taken aboard ships whose purpose was to destroy icebergs with explosives: these artefacts document the systems and choices that have led us to this point. In retrospect, they read like warnings, subtle evidence of a world nearing transformation.

TILL also carries an economic resonance: a cash drawer, a ledger, a reckoning. It becomes a symbol of extractive industry and ecological debt – the cost of progress, the total not yet paid. Till it’s too late. Beneath the surface lies a growing political charge. On the very day the artist finished scanning the papers used in the first version of TILL, the BBC reported on the Arctic as “low-hanging fruit” (22 May 2025) – a new frontier for geopolitical competition and resource extraction. What was once seen as wilderness is now reframed as opportunity – for investment, exploitation, and strategic gain.

But within the title is also a note of optimism. The sound of a tiller – the instrument used to steer a ship – suggesting that while this is a story of environmental loss, it is also one of agency. Think of us as ice – increasingly fragile, surrounded by warming waters – but able to chart a different course.

This film shows the studio during the creation of TILL, and the many found papers used as part of its composition, some of which originate from countries along the routes of the Tall Ships Races: a 1960s train ticket from Norway; letters posted to and from Scotland; French wartime ration cards and even correspondence with prisoners of war. Also find pages from newspapers; a handwritten holiday itinerary; a school essay on astrology; a heated exchange of telegrams between politicians; dozens of photographs of long-lost icebergs and glaciers; and, a letter sent from Tonga, now itself under threat from rising seas. There are also personal notes from the artist – reflections on the climate crisis and rising sea-levels. In Cass’s projects, the use of found, repurposed materials symbolises opportunity, and the importance of sustainability. Here, recycled papers were arranged digitally, meaning the same resources can be used again. These fragments offer glimpses into the fabric of everyday life, from the mundane to the monumental. Together, they form a chorus of human activity, unfolding during a fleeting window of planetary stability.

A Dive into the Data

TILL was produced using real Arctic ice measurements. The dataset spans from 1895 to 2025, recording the extent of Arctic summer sea ice (at the end of the season, every September), measured in millions of square kilometres. The early decades, drawn from ship-logs and historical records, show relative stability, with ice extent averaging between 8.0 and 9.0 million km². This persisted until the mid-20th century, when a gradual decline began. From the 1960s onward, the data reveals a clear downward trajectory, with the pace of loss accelerating sharply in the 1990s and 2000s. By 1990, the extent had already fallen to 5.98 million km², and by 2007, it dipped below 4.2 million km² for the first time.

Stills from the artwork can be seen above, including one from 2012 – a record low – when sea ice shrank to just 3.41 million km² – less than half the area observed a century earlier (NSIDC).

Recent records show a diminished Arctic. In 2023, the summer minimum was 4.23 million km², and in 2024, it reached 4.28 million km², placing both among the lowest extents on record – far below the 1981–2010 average of around 6.2 million km² (NSIDC, NASA Vital Signs). While these levels are above the 2012 minimum, they reflect not a recovery but the establishment of a new, lower baseline. Every year since 2007 ranks among the lowest in the satellite record. These figures not only measure ice lost, but the deepening imprint of industrial activity, fossil fuel use, and ocean warming.

This decline is more than a geophysical trend – it is a shift in planetary equilibrium. The Arctic has become the frontline of climate change, and as ice retreats, the region becomes increasingly vulnerable – as do we. What happens in the Arctic affects everywhere.