“Everything needs to change, and it has to start today…”

Reading List:

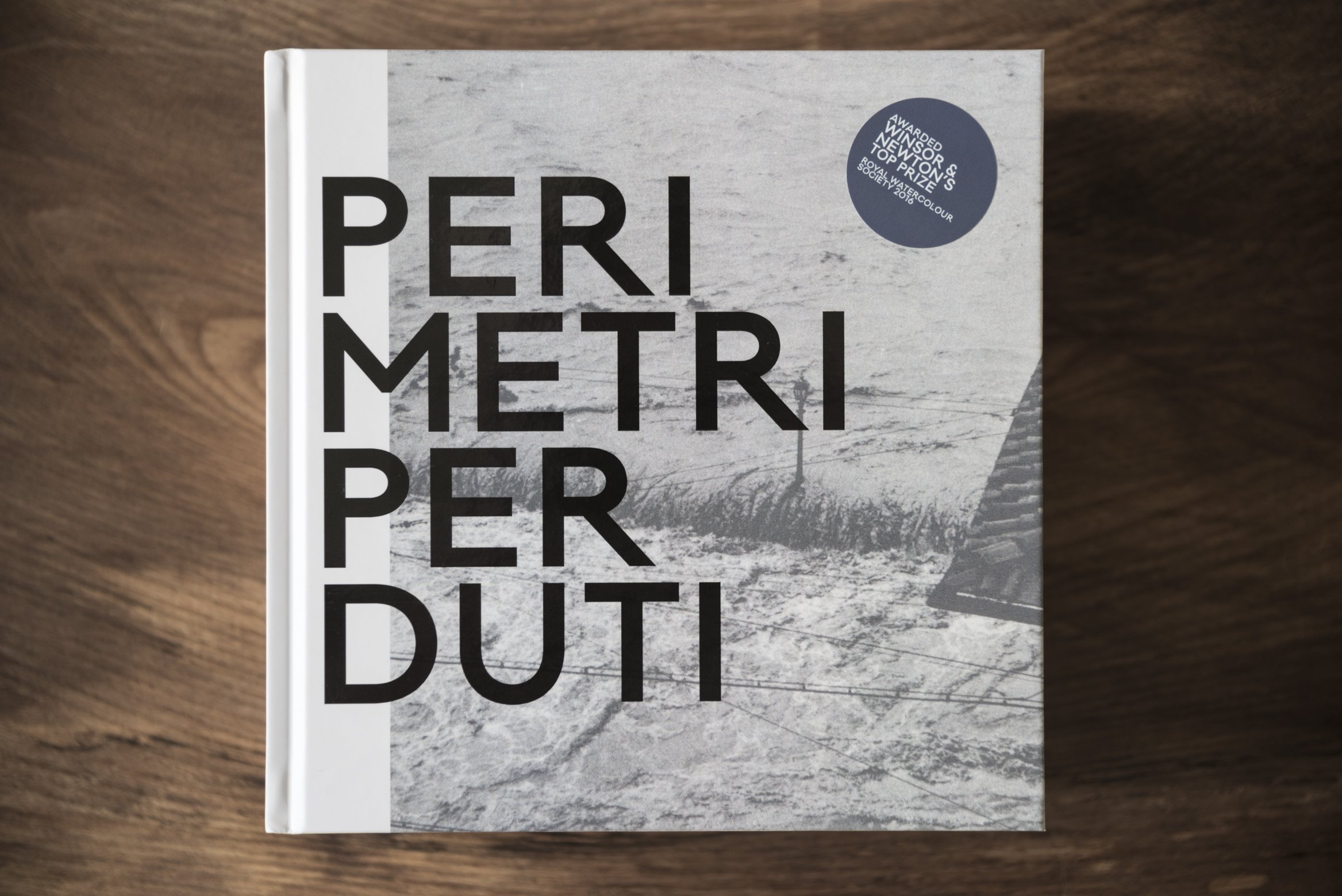

Exploring Topics Raised in

As Coastline is to Ocean

Some 600 miles south of Ullapool [where our exhibition has just closed] the idea for this post came after visiting Olafur Eliasson’s Tate Modern exhibition In Real Life.

London – where I live currently – is a city at risk in this time of climate crisis: facing flooding, water shortages and major subsidence. By 2050, summer temperatures will be on average 5.9 degrees hotter than they are today, pushing the recent – and irresponsibly media-celebrated – “record” temperatures well into the 40s.

The city’s art and culture therefore – its public events – now carry a heavier responsibility. Though this is by no means true of London alone; locations around the world will be – or are already being – affected by climate change.

Perhaps most scrutiny is applied to those already flying a green flag, such as Eliasson, now considered a beacon of the environmental art-form.

Eliasson’s In Real Life is a dynamic (if not quite immersive) journey through earth, ice and fire, but I regret leaving the exhibition without sensing a call to arms, despite visiting thrice. There was no urgent plea communicated, not to us nor our policy makers, and I was put off by the frantic scramble to capture its energetic curation by way of selfie and Instagram-story. Nevertheless, a bit of extra research – mostly provided by Eliasson himself via his Studio Alphabet – confirms the artist as an environmental advocate of the highest order. It might just be that the key works on show failed to move me personally.

The peripheral components of In Real Life piqued my curiosity more than the touted blue-chip artworks. These include the idea to ethically transform the menu of Tate’s restaurant; his Little Sun project; and (though this hasn’t been stated as a deciding factor) the artist’s influence in Tate’s declaration of gallery-wide climate emergency.

The most impressive of these extras comes in the form of a research wall. Here, the artist presents his alphabet, sharing with us important articles, books, artworks and projects linked to our changing Earth; many with transformative powers. This research wall has inspired the following reading list. It’s significantly smaller than Eliasson’s, but, contains a considered selection of books which have been important to me in recent months, and during the creation of As Coastline is to Ocean.

Contributions and recommendations also come from my fellow exhibitor Joseph Calleja; from the gallery team; and from marine scientist Ailsa McLellan who works to raise awareness of issues facing Scotland's coastline (Ailsa gave a talk during As Coastline is to Ocean on the importance of our “underwater forests”).

An Talla Solais has a history of environmentally attentive exhibitions, and the Ullapool community is particularly attuned to the to-and-fro between land and sea. In our short time there, we’ve heard not only of Ailsa’s talk, but of beach cleans, litter-cube building sessions, conservation workshops, a marine festival, a Photofest on the topic of Borders, an ecology focussed writing course and a workshop to create climate strike banners (for the International Climate Strike on 20th September). Ullapool is a forward-looking community, defining environmental restraint and respect.

“I have found that any perceived changes in my life have occurred because of my curiosity…”

The following reading list mentions seventeen titles, united in their (wide ranging) exploration of environmental themes: from scientific commentary on the climate crisis, to poetic exploration of our coastlines. While not all of the artworks on show in As Coastline is to Ocean aim to reference environmental change directly, my own studio work in recent months has evolved into subtle campaign around the climate crisis. My hope is that I can bring my audience along with me as I learn more on the issues facing our Earth: the following list is one effort to achieve this. In following the science behind climage change, we better understand how we have reached this point, and what must be done to harness our rising global average temperature.

No One is Too Small to Make a Difference

Greta Thunberg

Underland

Robert Macfarlane

The Uninhabitable Earth

David Wallace

The Water will Come

Jeff Goodell

Brave New Arctic

Mark C. Serreze

Out of Ice

Ogilvie, Warrilow, Patrizio, Heron, Ingold, Arends, A.Ogilvie, Decker, Macfarlane

This is not a Drill

Extinction Rebellion

The Human Planet

Mark Maslin + Simon Lewis

Anthropocene

Edward Burtynsky

A2B: An Artist’s Journey

Robert Callender + Ogilvie, Patrizio, Dunn, Warrilow, Johnston

Arctic Dreams + Horizon

Barry Lopez

The Unnatural History of the Sea

Callum Roberts

The Essential Guide to Rockpooling

Julie Hatcher + Steve Trewhella

Rock Pool: Extraordinary Encounters Between the Tides

Heather Buttivant

Monograph

Katie Paterson

Hotel Absence

Fiete Stolte

The first recommendation is the shortest, but packs the biggest punch. No One is Too Small to Make a Difference gathers the history-making speeches of young activist Greta Thunberg. In 2018, fifteen-year-old Thunberg decided not to go to school one day. Her actions ended up sparking a global movement for action on the climate crisis, inspiring millions to go on strike, forcing governments to listen, and earning her a Nobel Peace Prize nomination. The book is a rally-cry for why we must all wake up and fight to protect the planet, no matter who we are or how powerless we may feel. Thunberg is also quoted in the title of this blog entry; we must all be curious in order to influence change.

“If our house was falling apart, you wouldn’t hold three emergency Brexit summits, and no emergency summit regarding the breakdown of the climate and ecosystems.”

The next book offered as compliment to As Coastline is to Ocean is Underland by Robert Macfarlane. The book is both panorama, and intense study. Despite the fact that Macfarlane has focused his gaze on what lies beneath, the book soars. The locations Macfarlane traverses range from a dark-matter research station in a salt mine beneath the Yorkshire coast, to Paris’ subterranean labyrinths. From caves in the Mendips; to Olkiluoto Island on the Bothnian sea, where nuclear waste will see out its half-lives; and from the from the rivers that twist beneath the Carso plateau, to the fjords and glaciers of the Arctic, where once buried secrets are now exposed as ice departs.

These extraordinary tunnellings are merely springboards (peripheral vantage points) for discussions of a deeper and more emotional nature: the relationship between us and the Earth; and our place in what he describes as “deep time”. The author’s observations on land, coast and sea are far-reaching, with an inquisitive gaze similar to that of Eliasson’s. Macfarline makes clear that we have passed a turning point, that the climatic consequences of our rapid abuse of the Earth are now upon us.

Asides from sharing many of the environmental observations made in As Coastline is to Ocean, Macfarline also puts into words something Joseph and I discuss often: “trace fossils”. As artists working with found objects, we embrace what a collector might term “loveable scars.” In our exhibition booklet, Joseph writes of the workbench he inherited from his grandfather, etched with the work-scores, gouges and marks of three generations of Calleja. Macfarlane describes these as “the marks that the dead and the missed leave behind. Handwriting on an envelope; the wear on a wooden step left by footfall; the memory of a familiar gesture by someone gone, repeated so often it has worn its own groove in both air and mind: these are trace fossils.”

“Sometimes, in fact, all that is left behind by loss is trace – and sometimes empty volume can be easier to hold in the heart than presence itself.”

Macfarline labels us as custodians of an “empire of things … with its own unruly afterlife.” Just one such example is the finding of “plastiglomerates” – a new form of Anthropocene stone. These could be seen as the evolution of Robert Callender’s depictions of plastic beach-waste, formed of sun-melted plastic, landscape debris and organic matter. I wonder if Callender might have sculpted plastiglomerates as the next step on from Coastal Collection and Plastic Beach.

Bleaker in its outlook is The Uninhabitable Earth by David Wallace. Shifting between the darkly humorous – “eating organic is nice; but if your goal is to save the climate, your vote is much more important” – to despair over the United Nation’s prediction that we are on track for 4.5 degrees of warming by 2100 (following the path we are on today). Wallace serves us with point after point on where we’re headed. From the insurmountable:

“…we do not yet know how much suffering global warming will inflict. But the scale of devastation could make that debt enormous, by any measure. Larger, conceivably, than any historical debt owed one country, or one people by another, almost none of which are ever properly re-payed…”

To the baffling:

“…air conditioners and fans already account for 10% of global electricity consumption. Demand is expected to triple or perhaps quadruple by 2050. According to one estimate, the world will be adding 700 million A.C. units by just 2030. Another study suggests that by 2050 there will be, around the world, more than 9 billion cooling appliances of various kinds…”

You’re reading this blog post online, maybe on a phone, and Wallace has depressing commentary there too: “…much of the infrastructure of the internet could be drowned by sea level rise in less than two decades; and most of the smartphones we use to navigate it are today manufactured in Shenzhen, which, sitting right in the Pearl Delta, is likely to be flooded soon as well...”

Referencing The Water will Come by Jeff Goodell, Wallace runs through just a few of the monuments – in some cases, whole cultures – that will be transformed into underwater relics this century.

“Any beach you’ve ever visited … Facebook’s HQ … the Kennedy Space Centre … the US’s largest naval base … the entire nations of the Maldives and Marshall Islands … most of Bangladesh … all of Miami beach, and much of the south Florida paradise … St Mark’s Basilica in Venice … Venice Beach in Santa Monica … the Pennsylvania White House and Winter White House…”

Wallace observes that we’ve spent the millennia since Plato enamoured with a single drowned culture: Atlantis. “If Atlantis ever existed, it was probably a small archipelago of Mediterranean islands with a population of a few thousand.” By 2100, if we do not halt emissions, as much as 5% of the world’s population will be flooded every single year.

The answers to the key questions of our era – how much hotter will it get? By how much will sea levels rise? – are entirely human, that is, entirely political. How do we respond to the threats we are facing? We must urge our governments to act.

In Brave New Arctic by Mark C. Serreze we shift the focus to our planet’s thermostat – ground zero of climate-change – the Arctic. While this book is of a more scientific nature, what Serreze writes on the future of the polar region is disconcerting. Serreze describes a region which is out of control. Ice is shrinking and thinning, and we are facing ice-free Arctic summers. By 2050 – safely assuming no drastic reductions in greenhouse gas emissions in the immediate future – the Arctic Ocean will likely have little or no sea-ice at summer’s end.

“It is a foregone conclusion, that, in future generations – whether on the ocean or on the land – the Arctic will have much less ice. Winter darkness will still bring low temperatures and with them snow and ice, but this winter cold will have significantly faded … the snow that falls and the ice that grows in winter, will not survive the stronger summer warmth. That the Arctic Ocean will become free of sea ice in late summer and early autumn is a given. The only question is how quickly it will happen. Which will depend on the relative rolls of a warming atmosphere and a warming ocean; the vagaries of natural climate variability and how quickly greenhouse gas concentrations continue to rise.”

As someone who has spent his life reading Arctic data, even Serreze was taken aback when the region “reared up and roared.”

“Some of the greatest unknowns revolve around the impact of a transformed Arctic … will a warmer Arctic have significant impact on weather patterns on lower latitudes? Will this effect agricultural patterns? How quickly will sea level rise? Given prospects of increased shipping and extraction of resources, how much busier will the Arctic become? And, will this lead to conflicts? These are questions that should concern us all.”

What binds those mentioned thus far is a desire to raise awareness, to challenge our thinking, to urge communal action on environmental change. Artist Elizabeth Ogilvie questions through powerful display, whilst still inviting us in personally. Like Serreze, Ogilvie looks north. Most recently, through her impressive project (and publication) Out of Ice. Ogilvie – wife to our fellow exhibitor, the late Robert Callender – has spent her working life exploring water (though perhaps it’s more fitting to say simply her life, for she’s had a preoccupation with water since childhood). In recent years, her focus has been on ice.

Andrew Patrizio says of Ogilvie that she encourages people to see, not just to look, “to pay attention in a mindful way with the possibility that they then might act.” And, in the same way Robert Macfarlane describes the work of author Barry Lopez as “begin[ing] in the aesthetic”, yet “tend[ing] to the ethical”, the same is true of Ogilvie, who engages deeply with the topic of climate crisis, working on wide ranging collaborations, creating stunning water and film installations. Her work is part documentary, part poetry. The book she has co-produced includes insight into Inuit life, on building an igdlo, on prepping a sled; relations between ice and soil in the Anthropocene (that soil is “sealed … beneath layers of concrete and asphalt … banished to subterranean realms”); and crescendos in a series of pages exploring her exhibition of the same name in Ambika P3 gallery.

As I myself have aimed to do in several of my As Coastline is to Ocean artworks, Ogilvie approaches ice loss from peripheral vantage points. Though, it would be too much of a generalisation to state that this is a key feature of her work. She is inclusive in her commentary, offering wide ranging perspectives, in order to give her audience a more immersive experience.

“As the world looks north for indicators of its future, art gives the landscape visual and exportable form, allowing it to serve as beacon, message and reflection” – says Julie Decker in her contribution to Out of Ice. On discussing Ogilvie’s installation at Ambika P3 gallery, in which “the ice melted faster than expected” due to the body heat of guests, gallery director Katharine Heron states “…unlike the melting of the great ice caps in the polar areas, which too continues so much faster than anticipated, these blocks could indeed be replaced.”

In a change of pace, we move now to This is not a Drill by Extinction Rebellion. While Ogilvie’s work is deeply considered, to the last detail, XR present themselves quite differently, yet no less endearingly. Ogilvie draws her audience in sensitively, while XR aims to do the exact opposite, though of course, they are not presenting themselves as artists. The message is the same, however. We must act.

This is not a Drill is a short must-read for anyone unsure of XR’s aims or approaches. The book is is sincere and passionate, whilst also being informative. These are ordinary citizens who truly care, presenting themselves in unvarnished fashion, embracing the imperfections that such mass protest involves.

As the jacket-sleeve says:

“Extinction Rebellion is a global activist movement of ordinary people, demanding action from Governments. This is a book of truth and action. It has facts to arm you, stories to empower you, pages to fill in and pages to rip out, alongside instructions on how to rebel - from organising a roadblock to facing arrest.”

The beginnings of the Anthropocene will feed into the future stories we tell about ourselves and of human development.

“Human impacts are at the level of dictating the future of the only place in the universe where life is known to exist. This is a historic declaration...”

The Human Planet by Mark Maslin and Simon Lewis helps us to define the Anthropocene, and how it came about. That we are responsible for the rapid decline in our planet’s health is in no doubt…

“If you compressed the whole of Earth’s unimaginably long history into a single day, the first humans that looked like us would appear at less than four seconds to midnight. From our origins in Africa, we spread and settled on all the continents except Antarctica. Earth now supports 7.5 billion people, living on average longer and physically healthier lives than at any time in our history. In this brief time, we have created a globally integrated network of cultures of immense power. On this journey, we have also exterminated wildlife, cleared forests, planted crops, domesticated animals, released pollution, created new species and even delayed the next ice-age. Although geologically recent, our presence has had a profound impact on our home planet. We humans are not just influencing the present, for the first time in Earth’s 4.5 billion year history, a single species is increasingly dictating its future. In the past, meteorites, super volcanoes, and the slow tectonic movements of the continents radically altered the climate of Earth, and the life-forms that populated it. Now, there is a new force of nature changing earth – homo sapiens – the so called wise people”.

Since the dawn of the industrial revolution, we have released 2.2 trillion metric tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere – increasing levels by 44%. This is acidifying the world’s oceans and raising Earth’s temperature. Human actions are altering the global carbon cycle at a faster rate than when Earth transitioned from glacial, to inter-glacial conditions.

What we are doing to the Earth is unusual in the context of all of Earth’s history. As an example, “we humans have altered the global nitrogen cycles so fundamentally that the nearest realistic geological comparison is an event almost 2.5 billion years ago.”

We have known since the 1800s that our actions have clear and damaging environmental impacts, but corporations have continued to snub warning signs.

The chapter Fossil Fuels: the Second Energy Revolution is perhaps the book’s most important, succinctly summarising how we humans have ended up where we are today.

Edward Burtynsky’s Anthropocence is an ideal illustrative companion to The Human Planet.

Our fellow exhibitor, Robert Callender, is quoted as having said of his installation Plastic Beach – in the publication A2B: An Artist’s Journey – that it’s “for our children’s children’s children.” That it was designed “to draw attention in a graphic way to the grave state of our coastline. The horrific assortment of plastic is quite alarming. Debris is both commercial and domestic but primarily commercial, reflecting the nature of our society.”

Based on all that I’ve learned about Robert, I don’t think he would have appreciated me summing his work up in a blog post, so I won’t attempt to. Though it’s precisely because of reading A2B that I’ve been able to generate an impression of a man I haven’t met, yet whose work I have held foremost in mind for many months whilst working on As Coastline is to Ocean. The clarity and honesty that characterise his works, processes and indeed his life are potent in A2B.

Callender expressed the desire to produce this edition during the short illness leading to his death in 2011. The edition documents his key works, projects, research and studio. Encased within a beautifully designed folio, A2B includes a series of bound volumes, prints and a DVD, telling of his compelling vision. Callender’s work is highly attuned, matched in quality and depth by that of Elizabeth Ogilvie. Ogilvie – who oversaw production of the edition – has shown consideration at the highest level, balancing sophisticated layout in accordance with the never-over-indulgent work of her late husband.

Associate Director of An Talla Solais, Joanna Wright, adds Barry Lopez’s Arctic Dreams to the list. Joanna states that “Lopez’s long experience of the north brought a shift of perspective to how my western mind thinks about the natural world. I loved its insistence on noticing detail, and honesty about the contradictions we are tangled in and need to see a way through.” I would also add that Lopez’s latest auto-biographical work – Horizon – as an ideal follow up to Arctic Dreams, in which a life’s travels are re-visited and his Arctic commentary re-worked to match current day data.

Marine scientist Ailsa McLellan recommends two books: first, Callum Roberts’ The Unnatural History of the Sea, “providing a readable account of the horrible mismanagement of the sea and its resources – if only we could learn lessons from it.” And on a more light-hearted note, The Essential Guide to Rockpooling by Julie Hatcher and Steve Trewhella, which she describes as “just magic”, and “opening the door to exploring that most exciting bit where the sea meets the land.”

In the same spirit, An Talla Solais’ Geraldine Murray adds Rock Pool: Extraordinary Encounters Between the Tides by Heather Buttivant.

Joseph Calleja suggests artist Katie Paterson’s recently published Monograph: an elegantly composed volume grouping each of Paterson’s key projects to date. This body of works firmly places the artist at the forefront of art today. Paterson is wide ranging in her outlook, but her works can clearly be bound by a care for the Earth, and our place in it. Like Macfarlane, Paterson too looks to deep-time.

And to end on the theme of time, Fiete Stolte’s Hotel Absence is a revelation: in particular, descriptions of his eight day week project, in which the artist’s daily routine for almost three years ceased to obey the established rhythm of the 24-hour day, structured by the rising and setting of the sun. His days each lasted 21 hours; his week eight days…

If only we had this much extra time at our disposal to grab hold of our changing Earth.