Foreign

Familiar

Scottish Artists in Italy

A collection curated by David Cass, in collaboration with The Scottish Gallery & Robin McClure (for the David McClure Estate)

The Balmoral, Edinburgh; and online

Paintings illustrating locations that exist in the collective imagination and memory — chiefly Florence and Venice — discussing the notion of familiarity and placing the artist in the position of visitor.

Victoria Crowe's Night Lagoon Series • Oil on Linen • 12.5 x 12.5 cm

David Cass: La Porta d'Acqua Temporanei • Florence in Flood 1966 • Gouache on paper on wooden offcut

Elizabeth Blackadder

David Cass

Victoria Crowe

Joan Eardley (1921 - 1963)

Earl Haig (1918 - 2009)

David McClure (1926 - 1998)

William Wilson (1905 - 1972)

Text by Breeshey Gray & David Cass | April 2017

The paintings that form this collection draw inspiration from locations that exist in the collective imagination and memory — chiefly Florence and Venice. For that reason, the concept of familiarity surfaces, and with it, a discussion placing the artist in the position of visitor. Place is a theme present in each of these works. David Cass’s works (some 30 Venice oil paintings and a selection of Lucca drawings) are paired with gouache works by David McClure and anchored by artworks from Elizabeth Blackadder, Joan Eardley, Earl Haig, William Wilson and Victoria Crowe, who perhaps has more claim to familiarity as a part-time resident of Venice. Curated by David Cass, the exhibition presents work by Scottish artists who have each chosen ‘everyday’ Italy as subject matter.

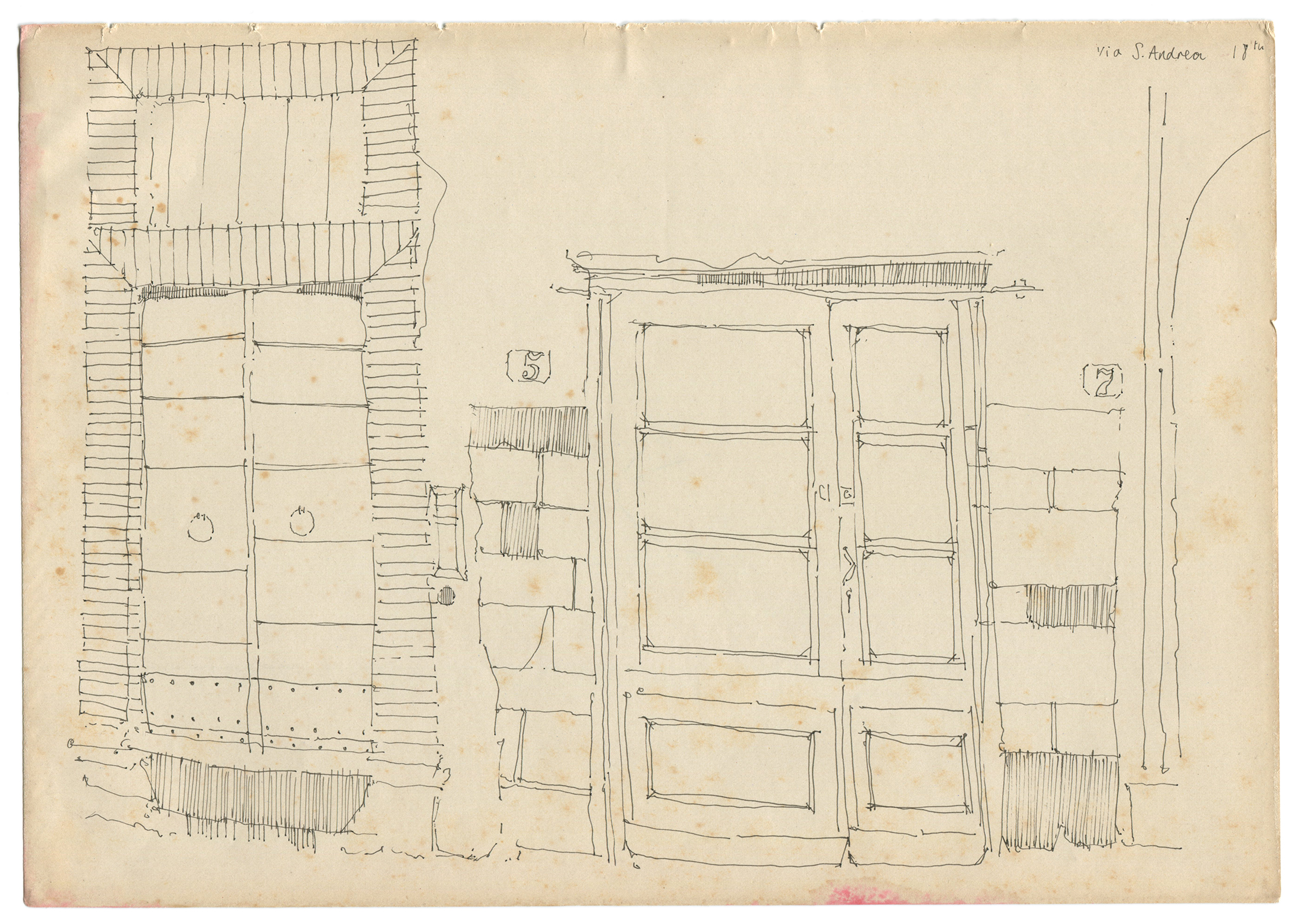

These artists have gone to great lengths to acquaint themselves with their chosen city’s fabric, presenting works that speak of process: created by deliberately repetitive methods, and challenging the relationship they have with places they have only — or, can only have — experienced for temporary periods. But for two paintings by Earl Haig, and Victoria Crowe’s ‘Tourists and a Very Wet Day’, these works avoid presenting the human form, yet evidence of human activity lies at the core of each work. From McClure’s paintings of covered Florentine market stalls to Cass’s recurring illustrations of intercoms and door handles, human presence is just outside each frame.

Cass’s cropped oil paintings offer an alternative look at the Venetian city interior. Like McClure's, these are exclusively front-facing works, presenting an exaggerated two-dimensional aspect, and primarily depicting ordinary architectural scenes. Cass’s Venice works feature no glimpse of sky, nor do they offer context. Many are fragments. They are paintings upon paintings — their previous brushwork, marks and details evident under the surface — echoing the textures of the city's layered façades. They chime with Crowe's 'Night Lagoon' series: pieces that similarly look downward and in great detail to examine the seemingly insignificant. Yet it is often these scenes that carry the most power. Crowe's lagoon paintings present the water that enters Venice as black and thick like oil. They carry a sense of foreboding: fear of the water’s authority over the city. Cass’s works take this notion a step further, acknowledging that Venice is today being destroyed not only by its age and the weight of all it has lived through, upon its plunged wooden-pile foundations, but also by the inundation of visitors, water taxis and giant cruise liners that visit each and every day.

In tandem with this topic, for the last few years Cass has been constructing a project describing and analysing, from a creative standpoint, the Florence inundation of 1966. Cass's piece [above] 'La Porta d'Acqua Temporanei' (translated as 'temporary water-door', inspired by Venetian canal doors) introduces a further take on the notion of familiarity — or, unfamiliarity — by presenting the upheaval a flood carries as a temporarily lost sense of place. Just 10 years before the flood, Wilson and McClure spent time creating artworks in the city. Italy was a different country in the 1950s, still in slow recovery from the Second World War. The Florence that Wilson and McClure explored would have been a very different one from that which we experience today, and the reason for that lies almost solely in tourism. In one photograph of McClure at work, he is seen painting in situ, from Piazzale Michelangelo. Today, to paint in one of Italy’s most visited squares might seem a daunting and stressful exercise, to say the least. Furthermore, painting on the street is banned in many parts of the city, as Cass discovered while on a Royal Scottish Academy scholarship to the city in 2010

David McClure: Church and Square, Fiesole 1956 • Gouache • 37 x 59 cm

Courtesy of the David McClure Estate • Photographs: David Cass

There is an elastic sense of time in the artworks that make this collection, a conversation between artists who have visited the same locations during different decades. Aesthetically, the works that speak most directly with Cass’s are those of David McClure, which carry the energy of his feverish production, as he acquainted himself with a foreign city, filtering and focussing his lens in 1956. The locations represented here are allowed to remain in the collective imagination, and it is that collective consciousness that keeps the attraction of these locations alive, even as the cities themselves suffer and the reality of their plight grows more evident. And even as the roles are reversed and residents begin to consider their own spaces as foreign.

Joan Eardley: Building, Palazzo Type • 1948-49 • Gouache • 49 x 42 cm • Contact The Scottish Gallery

The works that form this collection are observations of the foreign everyday through often overlooked architecture and city elements, and indeed scenarios that might not spring immediately to mind upon consideration of these locations. This is taken to a further extent in Eardley’s ‘Building, Palazzo Type’, for it was not only in Glasgow that the artist sought out derelict or dilapidated built-environment subjects. In this watercolour the noble proportions of a Florentine riverbank palazzo stand — quite unfamiliarly to the ancient structure — on unstable foundations, at a precarious angle, the rubble of restoration work all around, and with another isolated (spared) building standing exposed behind. Eardley here is documenting the extreme restoration works necessitated by the devastation Florence endured at the end of the Second World War. The Germans had blown-up buildings along the river and each of the bridges that crossed it, except for Ponte Vecchio, which Officer Gerhard Wolf had ordered to be spared for personal reasons. Eardley’s watercolour depicts Piazza di Santa Maria Sopearno — along Lungarno Torrigiani and just behind Ponte Vecchio — and focusses on the still-standing Palazzo Tempi. This work therefore celebrates this steadfast ochre palazzo, one of many that line the riverbank, built some-time in the early fifteenth century and then restored three hundred years later to take the form that Eardley describes. This beaming structure — owned by successive Florentine noble-families — has stood resolute throughout the city’s turbulent history of siege, political struggle, war and repeated flooding*. Eardley’s painting presents this bastion as etched into that same history and memory, as familiar to the city’s inhabitants today as it would have been four hundred years ago.

*During the lifetime of Palazzo Tempi, Florence has endured seventeen small floods, sixteen large floods, and seven exceptional ones: most recently that of 1966, as seen in Cass’s miniature gouache of rising water.

David McClure: Il Duomo, Florence, 1956 • Watercolour • 49 x 69 cm

Robin McClure on his father David McClure | March 2017

My father graduated from Edinburgh College of Art in 1952 and following his Travelling Scholarship to Spain and Italy taught at the college part-time from 1953. In 1955 he was awarded an Andrew Grant Fellowship allowing him to paint full-time for an extended period. I had been born in March that year and late 1955 and early 1956 saw him, accompanied by my mother Joyce and myself, working in Millport on the small island of Great Cumbrae in the Forth of Clyde. In the Spring of 1956 the experience of a cold Scottish winter was relieved by a rather bold move to Florence (where he had stayed during his Travelling Scholarship) and where we then spent six months to be followed by a further six in Casteldaccia near Palermo in Sicily. For the artist (and indeed the family) this was a hugely formative period.

A mixture of long-term logistics and financial necessity meant that the artist’s output during this year abroad was limited to works on paper, sketchbooks and other drawings but mostly gouaches. Not that works on paper were seen to any extent as having a lesser status than oil painting: for many major figures of the preceding generation of the Edinburgh School, works on paper formed a significant part of their exhibited work; William Gillies, John Maxwell, William Wilson, Henderson Blyth spring immediately to mind. In terms of pure gouache technique, however, McClure is perhaps closest to Anne Redpath with the medium used almost alla prima with no discernable underdrawing, its opaqueness giving the image a character closer to an oil painting rather than to, say, a pen or pencil drawing worked over with transparent washes of watercolour.

Having said that the earliest work in this group is one of a first few works he painted in Florence and these were in watercolour, here an archetypal view of the Duomo and Campanile is seen from the high view point of Piazzale Michelangelo. This is typical of his early works there, like those shown here painted in Piazza del Carmine and in Fiesole. These were executed on the spot, in front of the subject, more straightforward depictions of the architectural/townscape details of a particular place.

Our second group shown here, the four Palazzi works, see the artist moving from this approach to one where recorded elements and motifs are drawn on, simplified and abstracted and worked into compositions back in the artist’s studio.

Later in Sicily, the artist did in fact work in oils on Sicilian and some Florentine subjects. The final two pieces included in this exhibition are small oil monotypes taking the abstraction process a stage further, the naturally reversed images again based on gouaches from the Palazzi theme.

Towards the end of his stay in Sicily he held a solo exhibition in Palermo ranging across work from his whole trip and organized by the Circolo di Cultura there. Later, in 1957, he held his first solo exhibition in Scotland at Aitken Dott’s Scottish Gallery showing Italian and Sicilian subject matter including further oils painted back in Scotland as well as gouaches and pen drawings from Millport and some still life oils. It is appropriate therefore that this show was instigated by The Scottish Gallery.

Artworks courtesy of The Scottish Gallery, The McClure Estate & David Cass