I was asked by Artists & Climate Change to write the following article: to reflect on Rising Horizon, my studio practice, and – more generally – the power of art in raising environmental awareness. Today, artistic work about climate change is popping up all over the world, in all kinds of venues. The goal of Artists & Climate Change is to track these works and gather them in one place. It is both a study of what is being done, and a resource for anyone interested in the subject. Founded by Chantal Bilodeau – artistic director of The Arctic Cycle – the organisation believes deeply that what artists have to say about climate change will shape our values and behaviour for years to come.

We have passed the turning point in terms of environmental change. To achieve the colossal aims of reducing our global average temperature, slowing sea level rise and decarbonising the planet, we must all do what we can: no matter how seemingly insignificant our actions may seem. For artists, this truly does come down to making conscious choices between using acrylic (plastic) paints or natural (handmade and completely lead free) oils; toxic resins or eco-resin alternatives; turpentine or zest-based cleaners; new papers or recycled stock… even one’s studio lighting should be considered. Every decision counts.

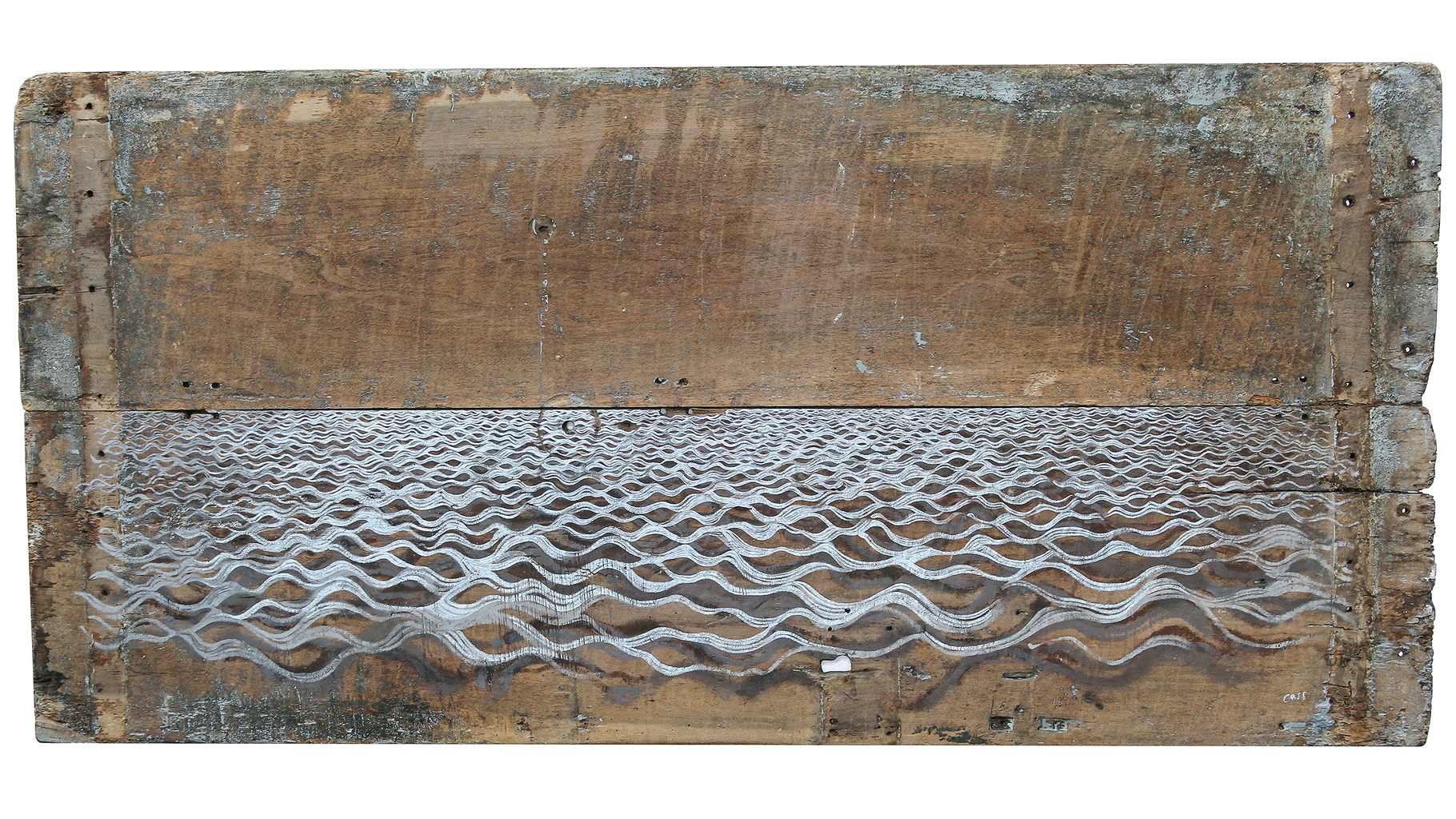

My most recent exhibition at The Scottish Gallery in Edinburgh – part of my ongoing series Rising Horizon – comprised over 150 paintings. The exhibition discussed sea rise and in the majority of the artworks, it did this not only visually but through material choices too.

Horizon 30% 2018–2019

Oil on repurposed metal sign · 60 x 30 cm

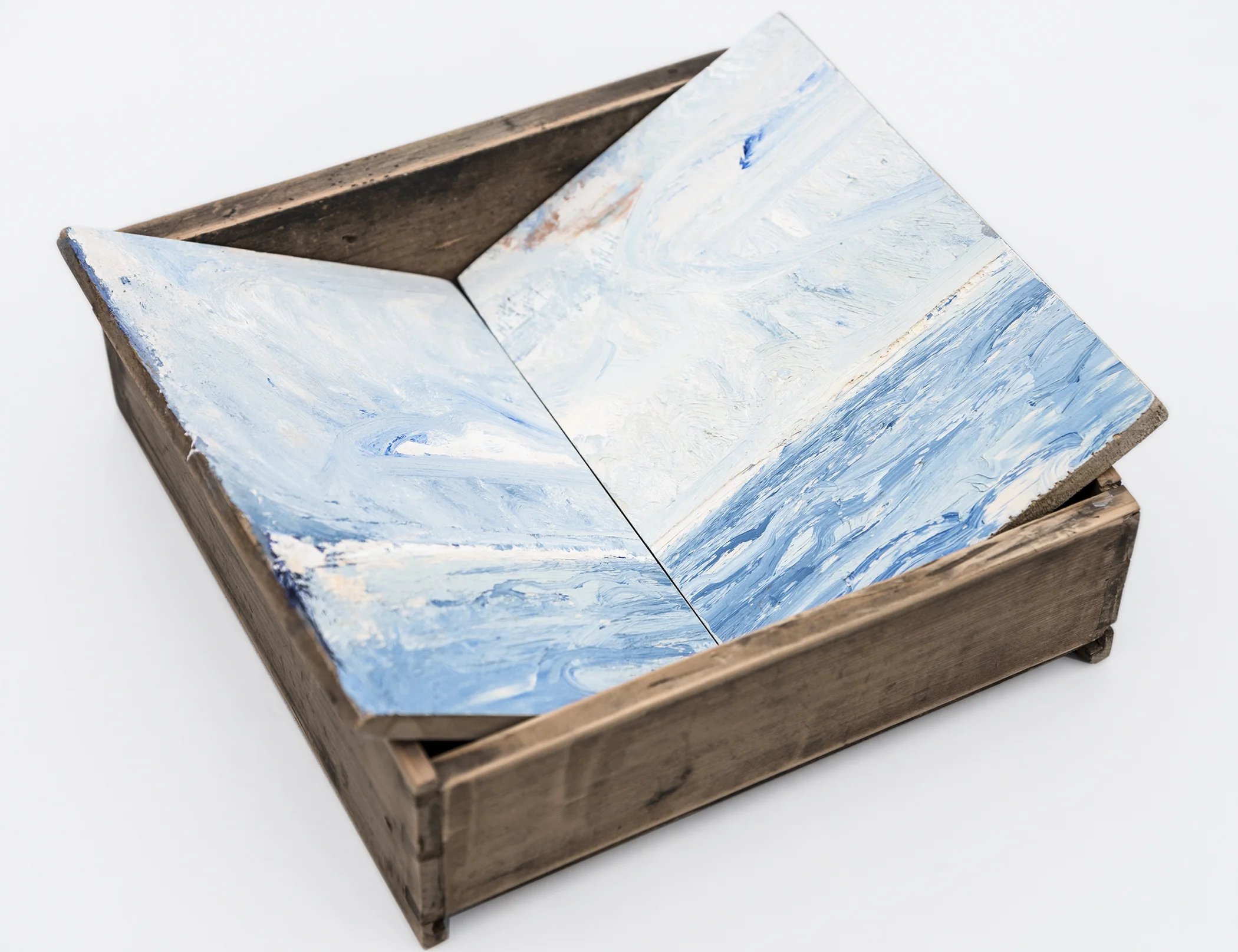

As an artist, I’ve received most coverage thus far for my repurposing of found objects – doors, table tops, drawers, street signs, matchboxes – into the foundations of paintings. These works have explored environmental themes both historic and contemporary. Every artwork I have created since leaving Edinburgh College of Art in 2010 has been made from recycled materials, and recently I’ve aimed to present commentary on sustainability and the need for a circular economy.

Rising Horizon was perhaps the most far-reaching (by this I mean non-site-specific) exhibition I’ve ever created. The series describes the coming global crisis that is sea level rise: not exclusive to any one coastline. True, we see certain locations already impacted but overall, the rise affects the World Ocean.

Rising Horizon followed another exhibition of mine which described Venice, Italy as an example of localised inundation: a result of environmental, anthropogenic change. The series examined the tide-marked brick and plaster façades of Venetian buildings as we see them today: still exquisite but eroding, stapled together, plastered with advertisements and often covered with graffitis admonishing cruise ships and tourists. Venetians are already feeling the impact of sea level rise: many have permanently evacuated their ground floors and basements. Others have had the foundations of their homes raised hydraulically. Underwater walls are treated with waterproof (ironically, plastic) resin.

This Venice series used the face as a vehicle to convey change, while Rising Horizon zooms out to illustrate, quite simply, a rising horizon line. The artworks in the show were hung so as to position the viewer within the exhibition: within the water. One simple goal behind the series overall, was to chart a gradually rising horizon-line, but we chose not to display the works along a linear path. In part, this was to mirror the non-linear way in which sea levels are rising. Ice melt, for example, is not a steady stream. Rather, run-offs happen in waves.

Horizon 20% 2018–2019

Oil on repurposed metal railway station sign · 31.5 x 79 cm

Scale and materials matter. Understated expression is important to me. Individually – no matter the scale, no matter how turbulent the sea surface – my paintings aim to be subtle. They do not shout. But when taken together, the obsession which lies underneath is evident. Surfaces are worked and re-worked, paint is applied and then removed and re-applied. This repetitive approach mirrors the functional past lives of the surfaces themselves: railway station signage (as above), motorway directional signs, tins and boxes, advertisement plaques… these items aren’t fragile, they were built to withstand time and the elements.

The paints are handmade (not by me, I should add) and the metal panels I painted upon for this show are recycled, reclaimed. I used these items to reference the impact of metal production on the environment: 6.5 percent of CO2 emissions derive from iron and steel production. Similarly, I painted upon panels made from re-formed plastic waste. One single square meter panel contains around 1,500 yogurt cups, for example. The World Economic Forum estimates that by 2050, plastics will be responsible for nearly 15 percent of global carbon emissions. This predicted increase will lead to plastics overtaking the aviation sector, which is currently accountable for 12 percent of global carbon emissions.

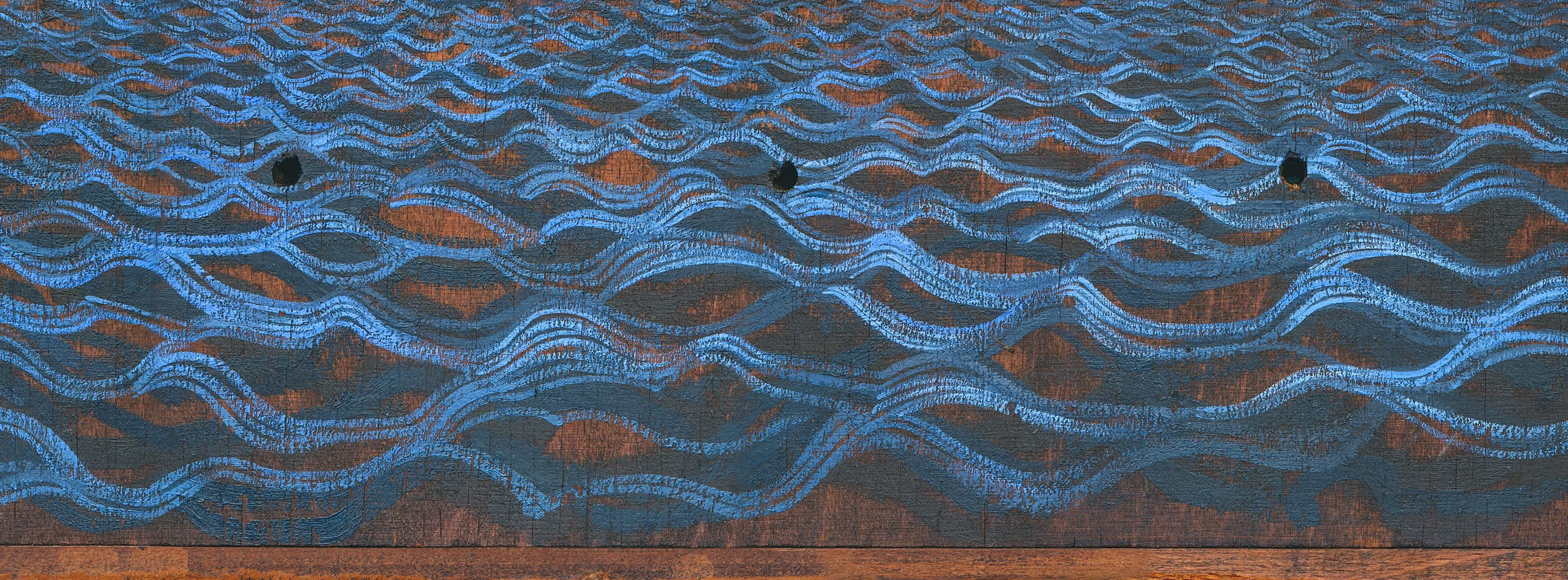

Horizon 42% (detail) 2017–2019

Oil & varnishes on repurposed copper boiler · 79 x 70 x 30 cm

Certainly, the most discussed piece in the show was a painted copper boiler. Titled Horizon 42% (opposite) this piece directly references the warming of (sea)water. The percentage is the proportion which thermal expansion contributes to overall sea level rise. It’s also the target of Scotland, my home country, which aims for a 42% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2020 (and an 80% reduction by 2050). An apt metaphor, as the boiler itself came from a Scottish home.

We dismantled the exhibition on February 25 and 26. Those were the warmest winter days on record in the UK. Radio stations were asking “how high will it get?” and the media used headlines like “UK basks in warmest February on record.” One newspaper dubbed the month “FABruary.” The media narrative was all wrong: this was not normal. At this exact time the previous year, we’d been suffering from extreme snow. The record-breaking temperatures should have been cause for alarm, not celebration.

Artists need to contribute to the global and growing bank of environmentally conscious artworks that carry a responsible narrative. The fact that art has the potential to convey messages makes it an essential tool for society. The Artists & Climate Change website is one perfect example of the power of art.

Throughout the exhibition, I witnessed public appetite for bitesize environmental facts. My work will continue to explore themes of change; indeed, my next project is a collaboration with fine artist Joseph Calleja, in partnership with the estate of artist Robert Callender. We are exhibiting a series of works in An Talla Solais gallery in Ullapool, Scotland, and we’ve just launched an Open Call, seeking works from artists in response to environmental change. Consider applying (there’s no fee).

I have also just launched a petition. Given my location, it is UK-based but my hope is that it will gauge public interest in having a regular Environment News broadcast on radio. Here in the UK, we really are not hearing enough about climate change in mainstream news.

Horizon 40% 2017–2018

Oil on repurposed metal engine-oil sign · 80 x 120 cm (framed)

Breif bio by Chantal Bilodeau | Cass’ graduation exhibition at Edinburgh College of Art (2010) was created using exclusively recycled materials. As a result of that show, he received a Royal Scottish Academy scholarship to Florence, where he combined this process of re-purposing with topics relating to environmental extremes. He spent four years exploring the history and legacy of Florence’s 1966 Great Flood, which led him to Venice and a study of its rising lagoon. Soon after, working in the Almería arid-zone, he added the topic of drought to the exchange. His recent projects (such as Rising Horizon) are more universal in their environmental outlook. They take the form of paintings, drawings, collages and sculptures – never using new materials.